The storyline is all too familiar: the PRD (product spec) is written, design begins in Figma, and a few iterations in, some big “gotcha” moment rears its ugly head. Oops. We all forgot about that thing, and now we have to adjust the entire flow and possibly change some requirements. Wasted time. Another familiar one: after the PRD is written, the PM tells the designer that they need these designs completed in two weeks, otherwise “eng will be blocked.” The designer agrees, despite a vague gut feeling that this might not be a two-week long project. This stressed out designer might put in some overtime hours, not wanting to disappoint their PM or be the cause of an engineer sitting around twiddling their thumbs. But in the end, the work is either subpar because corners were cut, or it ends up taking longer than two weeks anyway. Painful no matter how you slice it.

Here’s the thing – in the first scenario, that “gotcha” moment was probably something the team could have anticipated had they put more thought into what was going to happen once Figma was opened. And in the second scenario, it was never a two-week long design project, at least in the way it was scoped. If the PM asked the designer how much time they think they would have needed for the work, the designer probably would have given a different answer, taking into account the needs of the work.

I’ve seen the aforementioned scenarios play out more times than I’d like –– and at many different companies nonetheless. I started to realize that if designers took a moment to plan out their work before jumping into it, we might have better outcomes: less thrash, less wasted time, less burnout for designers, and better quality solutions for users.

I call it Design Planning – it’s the “let’s take a beat and think about the work we’re about to do, so we can make this more efficient and less painful” part of the process (“Design Planning” is cuter, right?). It provides a structured step after a PRD is written but before design begins.

The design brief is a guided reflection exercise for the designer, asking them to connect the dots between what’s in the PRD, what’s already flowing in their head, and what the design work is going to need, based on their expertise and product knowledge. The designer is asked to break the design work down into different parts, consider what they will and will not explore in Figma, and then document what questions they’ll answer with the design process in Figma.

Ideally, the design brief is part of the PRD, to reinforce the idea that this is all part of the product development process (one team, one dream, ya know?). But it can also be treated as a separate document.

Here’s an example to illustrate what part of this might look like:

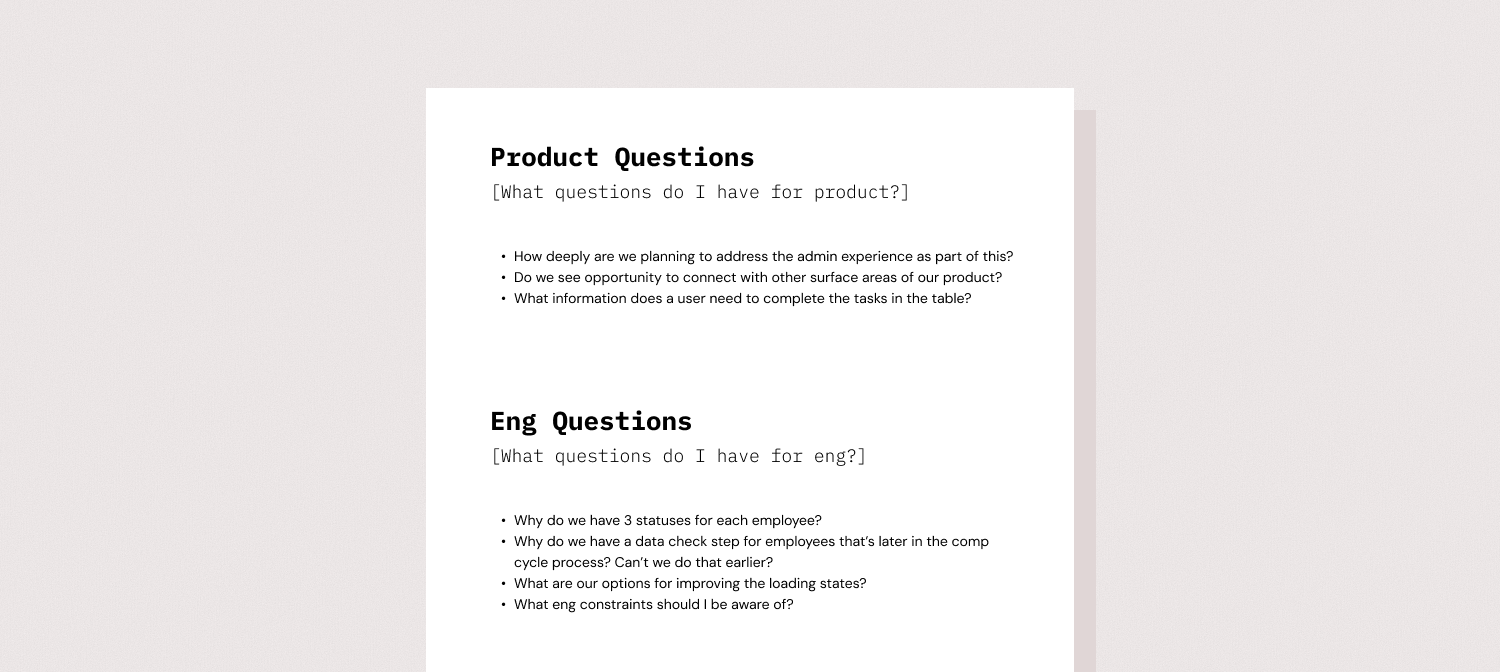

They will also jot down what additional information they need from product, eng, data, or other stakeholders, in order to start design work. After designers document their thinking in the brief, there are almost always more questions to be answered, which means the process is working! These are the gaps that would have become the “gotcha” moments, or the extra week of work that no one accounted for. Here’s what that part could look like:

Next comes the design timeline. Instead of this being led by when engineers “need work,” or when the PM thinks the work should be done by, ideally the timeline should be influenced by the content of the design brief. (Caveat: in a world where there are external deadlines or other factors, the needs of the design work need to be weighed with the other factors – and usually the answer is going to be to cut scope or lower the quality bar.) The designer is able to look at the work they’ve outlined for themselves, and ballpark the amount of time this work will need, taking into account real life: days off, other work they’re doing, design critiques, iteration, and heavy meeting days. As with the design brief, sharing the design timeline and getting feedback and alignment on it from your cross-functional peers is an important step here. That way, everyone is going into the work with the same expectations, not just on roughly how long the work will take, but the "why" behind it.

Here’s an example of a design timeline created by someone on my team:

I can (and will) write an entire post about crafting design timelines, but the main things to keep in mind are:

Over the last 5+ years that I’ve been coaching designers and educating other disciplines on Design Planning, it’s proven itself valuable time and time again. Teams that go through this process are not blindly trying to ship, ship, ship at all costs. They are not making decisions solely focused on ensuring engineers have high-impact work to do. Instead, they are taking the time to make sure they know the ins and outs of how the PRD translates into an exceptional user experience, and ensuring that the designer has what they need (time, user insights, context from eng) in order to create that user experience, ultimately delivering better business outcomes. These teams are also working more collaboratively – creating a transparent, shared space for all functions to align with design before execution begins. And finally, these teams are able to align up front with design on roughly how long the work is likely to take, given everything they know about it, so everyone can plan better. This means less thrash, less frustration, and more efficient work.

To put a bow on it, jumping from PRD to Figma has its risks, and they can often be costly. As a bonus, the design planning process helps empower designers to be leaders of their product development process.

I’ll leave you with a few things I’ve repeated many times in my career as a design leader, as I feel them deep in my core: Words are cheap, Figma is expensive. Figure out as much as you can in words before jumping into Figma. If we’re optimizing for making work for engineers, we’re doing it wrong. We need to be optimizing for our users. And finally, sometimes you need to slow down to speed up. When people hear “more process, more writing” they worry things will take longer. But the truth is, thrash and misalignment slow you down.

It’s clarity that speeds things up.

Check out my handy design brief template, which has all the questions a designer needs to get started design planning!